- Home

- Learn About Antique Furniture and Reproductions

- Resources

- The Long and Ancient History of Bookcases

The Long and Ancient History of Bookcases

The history of bookcases is a long and interesting one. Originally, books were written by hand, so they couldn't be produced in mass quantities like they are today. Since there weren't very many books, they would be carried in small boxes or chests by the wealthy aristocrats or clergy who typically owned them. As volumes of manuscripts were collected in homes of the wealthy and religious houses, people started storing the manuscripts on shelves or in cupboards. This is the earliest iteration of a modern bookcase that we see in history: once the doors of the cupboards were removed, the evolution of the modern bookcase really began. Even when people started storing books on shelves or in cupboards, they didn't arrange them the way we arrange our books today, all facing one way with the spines out for easy title-reading. Instead, they were placed in piles or laid on their sides, and if they did stand upright on the shelves, they faced the opposite direction, with their spines against the back of the bookshelf and the pages facing outward. Before titles were written on spines, they were actually written on the books' fore-edges, which are the edges of the book that readers use to thumb through the pages. The fore-edge of a book is the edge made up by the book's pages opposite of the spine. It wasn't until books became more accessible to all peoples via the invention of printing that titles began to be written on a book's spine instead. When that trend shifted, people started arranging the books on their shelves and cupboards in a manner similar to the way we display our books today. Early bookcases were usually made of oak, and oak bookshelves are still a staple of libraries that are considered elegant. The oldest bookcases in England are the ones in Bodleian Library at Oxford University; they were placed there in the last year or two of the 16th century. In Bodleian Library are the earliest examples of shelved galleries that still exist over the flat-wall cases. The long range of bookshelves in this library tend to be very plain and simple, though many attempts have been made to liven up the cases with carved cornices and pilasters. These attempts were most successful in the hands of English cabinet makers during the second half of the 18th century.

Private libraries first appeared in the early Roman Empire. Seneca the Younger spoke with great frustration about the way illiterate upperclassmen would decorate their homes with libraries even though they didn't read the books they owned. Bookcases in this time were referred to as Armaria. They were a kind of closed, labeled cupboard. The Armaria that Seneca complained about were made of citrus wood inlaid with ivory that ran to the ceiling. His complaints were recorded during his lifetime, probably between AD 4-60.

Thomas Chippendale (1718-1779) and Thomas Sheraton (1751-1806) made and designed many bookcases of great charm or elegance, mostly glazed with little lozenges encased in fretwork frames. In the eyes of some, the grace of Sheraton's satinwood bookcases has rarely been equaled.

In 1876, John Danner invented a revolving bookcase with a patented "pivot and post" design. The ingenuity of his work laid in the amount of space his bookshelf provided: thirty-two volumes of the American Cyclopedia could be stored in a compact space, readily available for perusal at the touch of a finger. Danner's bookcase appeared in the 1894 Montgomery Ward catalog, and he won a gold medal for his exhibition of bookcases at the 1878 Paris International Exhibition. The John Danner Manufacturing Company was known for its honorable workmanship and affordability, using woods like oak, black walnut, western ash, and Philippine mahogany.

For the traveling barrister (a type of lawyer), a specialized form of a portable bookcase was developed. It consists of several separate shelf units that may be stacked together to form a cabinet; it also includes a plinth and hood to complete the piece. When moving chambers, each shelf is carried separately without needing to remove its contents and becomes a carrying-case full of books. To help keep the books from falling out when being carried, a barrister's bookcase has glazed doors. As the shelves must still separate, the usual hinged door opening sideways cannot be used; instead, there is an "up and over" mechanism on each shelf. The better quality cases use a metal scissor mechanism inside the shelves to ensure that the doors move parallel to each other without skewing and/or jamming. Many bookcases in this style were made and exported worldwide by the Skandia Furniture Company around the beginning of the 20th century.

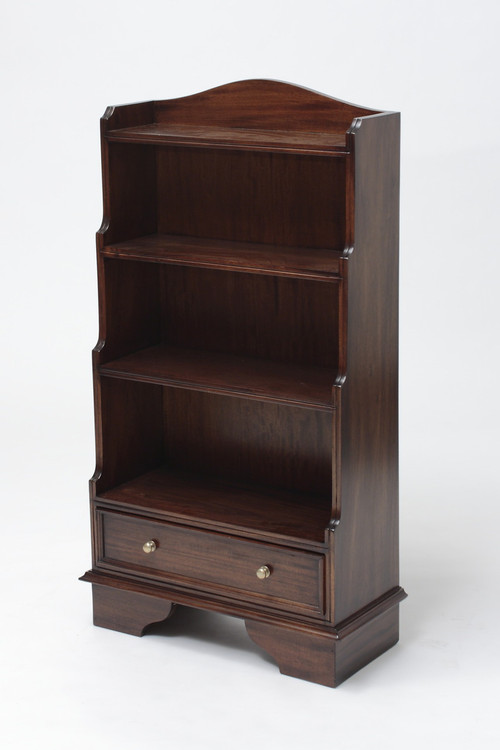

Thomas Jefferson's book boxes are similar to the barrister's bookcase. According to historical records, when the British burned down the capitol in 1814, Congress went into negotiations with Thomas Jefferson to purchase his personal library of about 6,700 books. This book collection became the foundation of the Library of Congress and had its own specially designed shelves to help transfer the books with ease from Thomas Jefferson's home. The book boxes were made of pine with backs and shelves but had no fronts. They were designed to be three-tier, stacked on top of each other. When fully assembled, the boxes stood about 9 feet high, but each shelf had a different depth, ranging from 13 inches to 5.75 inches deep. Bookcases are seemingly timeless, but they teem with a rich history of elegance and resourcefulness. To find your next bookcase, browse our collection of vintage pieces at Laurel Crown. We guarantee that the quality of our work will last for years and years to come.